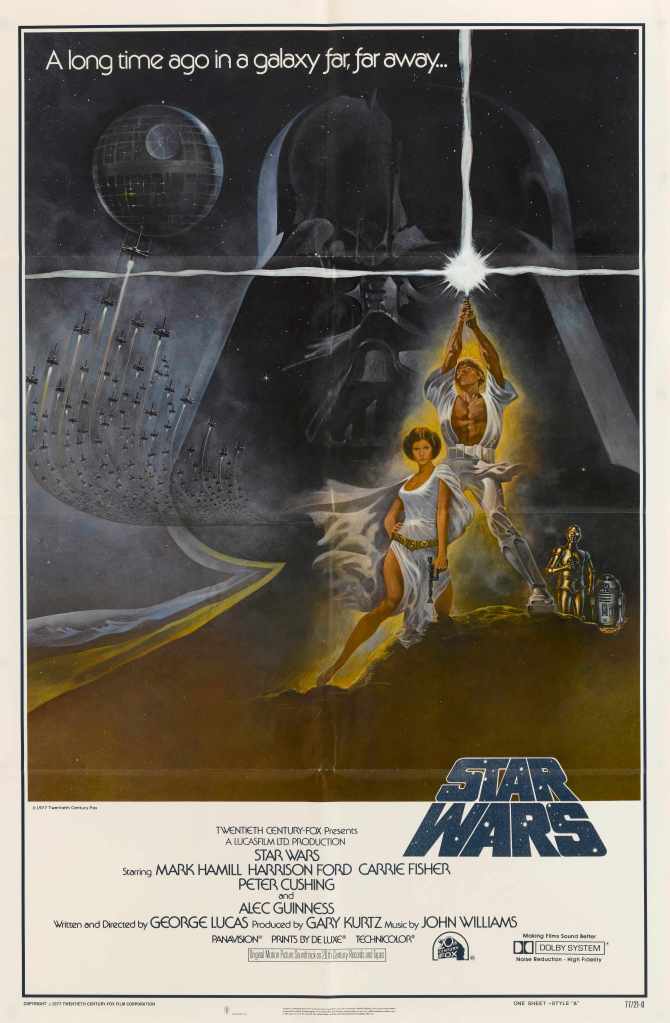

In 1977 George Lucas’ Star Wars was released in cinemas and is now recognised as one of the most successful and influential franchises in motion picture history. One of the reasons for Lucas’ success was his ability to tell a story that is both familiar and at the same time completely new. He did this by using common themes that occur throughout history and across cultures in a story that was set “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

At this point, you might be confused about how the subjects of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and Star Wars overlap… well; Carl Jung was a huge influence on Joseph Campbell, who went on to influence George Lucas.

Knowing this we can examine the common themes through the eyes of Carl Jung, who would refer to them as archetypes. Jung believed that these archetypes existed in our unconscious and by learning to integrate our conscious mind and unconscious mind we gain clarity of who we are. He would also relate the issues of his patients to mythologies in order to get a better understanding, meaning in reverse we can use analytical psychology to get a better understanding of modern mythologies, such as Star Wars.

If we focus on the original trilogy, the most obvious archetype is ‘The Hero’, found in our protagonist Luke Skywalker. I’m sure we’ve all heard stories of the brave hero that slays the dragon and rescues the princess. Luke’s quest could be transferred onto pretty much any hero you’ve ever heard of.

The second archetype, ‘The Shadow’ appears in both Luke’s companion Han Solo, and his estranged father Darth Vader. The shadow is the part of our unconscious that embodies all of our most undesirable traits, and until we learn to integrate them into our day to day life we will never be complete. Han is shown as Luke’s shadow through his arrogance, his ability as a fighter and worldliness; whereas the protagonist starts his journey as an unassuming, naive young man who can’t fight. Although in the case of Darth Vader, the antagonist, we can see a much harsher, angrier and animalistic figure with a lot of similarities to Luke.

Darth Vader is also a great example of what happens when you try to run from ‘The Shadow’, as he was once a good man who wanted to do nothing but protect the love of his life in a way that he couldn’t protect his mother. This eventually drove him to darkness, resulting in him murdering the woman he only wanted to protect (as well as loads of little kids in a temple).

Side note: the connection between Darth Vaders mother and his lover could be explained by Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex. The collaborator of Carl Jung believed that all men wanted to have sex with their mothers and kill their fathers… which in a way he kind of did if you blame his immaculate conception on ‘The Force’.

Back to business; the second archetype is ‘The Anima/Animus’, which can be seen in Star Wars through Princess Leia. This archetype differs depending on your gender; if you are a man you have an Anima that represents your feminine side, and if you are a woman you have an Animus that represents your masculine side. This archetype is often seen at first as an object of sexual desire; but you accept the Anima as a guide, and in the case of Luke his twin sister (disgusting I know), you become a step closer to your goal.

Leia works as a guide to Luke to assist him on his journey to find another archetype which is ‘The Senex’, characters that often take the form of an old man and play the role of a teacher. With the help of Leia, Luke finds his teacher in Obi-Wan and eventually Yoda.

By learning to embrace all of these archetypes Luke becomes a ‘Jedi Master’ and puts an end to ‘The Empire’. This is a metaphor for unification between the conscious and unconscious mind.

It’s important to keep in mind that Jung believed that there are as many archetypes as there are situations in life, so it would be impossible for a series of films to cover all of them.